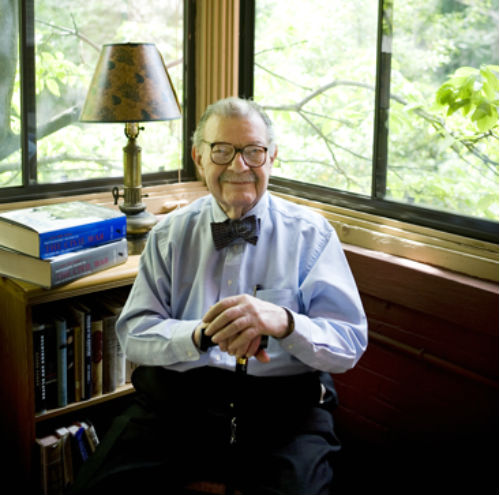

Everett Ortner, who passed away in May, was one of the most influential leaders of the revival of Park Slope and of older urban areas across the country. Working with his wife, Evelyn, he devoted his energies to transforming a community on the downswing since the 1960s into the vibrant Park Slope we know today, and to ensuring that the neighborhood remained a great place to live for years to come.

His efforts to bring about this dramatic change touched the lives of many. Here we present a few of their memories.

The obituaries and tributes published after Everett H. Ortner’s death at age 92 listed many of the milestones in his life: his birth in Lowell, Mass., in 1919; graduation from the University of Arkansas in 1939; his heroic service during World War II that led to his being awarded the Bronze Star with a “V for valor”; his harsh imprisonment as a prisoner of war; his 33-year editorial career with Popular Science magazine. Also mentioned was his marriage to Evelyn in 1953, as well as their purchase of a Park Slope brownstone a decade later. The numerous organizations that Everett belonged to, and the prominent roles that he and his wife played in what has come to be called the Brownstone Revival Movement, were also cited. Yet some important parts of his long life story were missing.

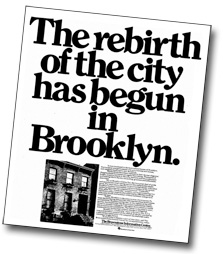

In 1963, when Everett and Evelyn moved to Park Slope, the neighborhood was in decline. Crime had become a serious problem, landlords were losing tenants, rooming houses were being abandoned, and many brownstones were for sale by homeowners who wanted to leave the neighborhood. Nonetheless, the Ortners purchased their house on Berkeley Place, largely because it retained much of its original detail, so that their Victorian furnishings would have an appropriate setting.

At that time, there was a consensus that the only way to restore Park Slope into an attractive, vital community would be by enticing people to purchase, renovate, and move into the houses that were for sale, including those that had been abandoned. Even as Park Slope residents were bemoaning the neighborhood’s decline, however, little was being done to reverse the trend.

When Everett and Evelyn joined the Park Slope Civic Council and began publicizing its house tours, they knew much more had to be done to encourage people to move here. Few outside of Brooklyn were aware of the existence of Park Slope, let alone that it contained many brownstones that could be transformed into handsome homes at a reasonable cost.

The Ortners, Joe Ferris, and a few other like-minded residents tackled this problem by conducting three different tours of Park Slope houses: one focusing on houses for sale needing work, another for those under renovation, and a third for the few that had been fully refurbished. They also encouraged the Brooklyn Union Gas Co. (now National Grid) to purchase and transform a dilapidated brownstone on Berkeley Place into a modern two-family home featuring a variety of gas appliances.

Everett also worked with the gas company to organize fairs for potential homebuyers that included bus tours of several brownstone neighborhoods. The fairs demonstrated how one could acquire and turn an old, worn-out row house into a lovely, modern home in an attractive community, minutes from Manhattan, and all at a reasonable cost.

Another major impediment to buying a brownstone that the Ortners tackled came from experience. “When we wanted to buy our house in Park Slope,” he said, “we went to 12 banks before we could get a mortgage.” At that time, almost all banks were unwilling to provide mortgages for row houses in any of Brooklyn’s integrated historic neighborhoods. Everett confronted the redlining problem by writing a letter to David Rockefeller asking why Chase Manhattan Bank wouldn’t mortgage brownstones. In response, he was invited to meet with the head of the bank’s mortgage lending. After several discussions, Chase committed to $100 million in community mortgage lending in New York City.

Everett and Evelyn also led a successful effort to change the thinking of mortgage officers in other banks by hosting several cocktail parties for them in handsomely renovated brownstones. Through his contacts with senior mortgage officers, Everett often helped buyers obtain loans when their mortgage applications were rejected.

The Ortners also had the foresight to anticipate problems that would come with a successful revitalization. They recognized that an influx of new homeowners would be quickly followed by real estate developers, and that renovations of brownstones might not always be in keeping with the appearance of the neighborhood. This led to their efforts to protect Park Slope from irresponsible development and alterations by working with the Landmarks Preservation Commission to create a historic district in Park Slope.

The agency indicated that, even though it wanted to landmark much of the neighborhood, it had only a small staff to do the required research. Everett, Evelyn, William Younger, and several neighborhood volunteers helped speed up the process by identifying, researching, and photographing the buildings on these blocks. (You can download the designation report at on.nyc.gov/1973-Park-Slope-report.) As a result, almost a quarter of Park Slope was landmarked in 1973.

The published tributes to Everett Ortner also left out another important aspect. Besides changing Park Slope, he and Evelyn transformed the lives of the many families who moved here in the 1960s and 1970s. Had we not moved to Park Slope, most of us would have led very different lives, remaining apartment dwellers in Manhattan or becoming homeowners in the suburbs. Instead, we came to Park Slope and created an incredibly close-knit community.

Life-long friendships were formed with many of the neighbors whom we met in the playgrounds, at block association meetings, and on lines waiting for our children after school. We shared backyards, tools, renovation ideas, and recipes. We helped one another with construction projects and babysitting. We agonized over child-rearing techniques, school choices, and which pediatricians and contractors to use. We shared potluck meals, exchanged house keys, and served as parental surrogates during emergencies. We established active block associations, a political club, the Food Coop, and several nursery schools.

Our block parties were something to behold. On Berkeley Place, children acted in plays, participated in contests, and played games while their parents socialized over drinks on the stoops. Block cleanups were annual affairs and block patrols were occasional events. Over the years we celebrated the births, graduations, and weddings of our neighbors’ children and recently, the births of our neighbors’ grandchildren. Surprisingly, many of us who moved here in the early years are still here.

Everett and Evelyn Ortner did more than change our lives — they enriched our lives. Their legacy is the Park Slope community of today.

— John Casson is a trustee of the Civic Council and a Park Slope resident for more than four decades.

The Power of Everett

I only had the good fortune to know Everett Ortner for the last 15 years. When he first asked if Green-Wood Cemetery could use some young volunteers to help with preservation efforts, I readily accepted. Yet I wondered why young French people would pay their own way to the United States and then be willing to work for free. Well, I just did not know the persuasive powers of Everett Ortner, and every year since 2002 we have had at least a half-dozen wonderful young people here working on various projects.

One of my fondest memories of Everett took place shortly after we lost Evelyn in 2006. Everett was visiting Green-Wood, checking up on his charges. They were working on the mausoleum of Dr. Valentine Mott, a prominent surgeon who, upon hearing that President Lincoln had been assassinated, took ill and never recovered. We had to negotiate a steep bank to reach the mausoleum, and there were no stairs in sight. I offered a hand, but Everett would have none of it. Employing his walking stick, he climbed the bank to get in the faces of his young disciples, urging them on to work harder. Classic Everett!

When Evelyn passed, the inseparable couple that they were, I thought Everett would join her rather quickly. Again, I underestimated the power of Everett. He still had work to do. He had to make sure that Preservation Volunteers was in good hands. Over time, he passed the reins to the remarkable Dexter Guerrieri and made certain that Preservation Volunteers will live on as a perpetual tribute to the Ortners.

— Richard J. Moylan is president of the Green-Wood Cemetery.

Tireless

Few private citizens have had the impact on New York City that Everett Ortner achieved. His vision, shared and supported by his late wife, Evelyn, transformed not only Park Slope but also brownstone neighborhoods throughout the city.

It was daring to invest in a Brooklyn brownstone when the Ortners bought theirs. It took charm and tenacity to persuade others to join them. And Everett had a day job. In later years, Everett was a dapper and enthusiastic presence at preservation events — encouraging others to fight on and modestly accepting the awards and thanks offered.

Everett also saw the need to involve the next generation. He worked with our late architect Roger Lang and sketched out plans for a volunteer organization that would recruit young people and let them get hands-on experience in historic preservation projects.

Both Everett and Evelyn were tireless boosters of historic districts, and believed in the benefits and rewards of urban living in older houses. Thanks to them, thousands of others now share those benefits.

— Peg Breen is president of the New York Landmarks Conservancy.

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Long before I’d met Everett Ortner, and long before I knew what a “preservationist” was, I had become one. I’d explored the hidden alleys of Boston’s Beacon Hill, the grand boulevards of the Back Bay, the quiet squares of the South End. But I had no knowledge of preservation as a cause. The beauty and the deep sense of place that these old buildings exuded was so powerful, so profound, that it was inconceivable they could ever be threatened.

Some years later I steeped in the history of my wife’s parents’ row house in Brooklyn Heights. They had helped to fight the early preservation battles against the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who back then were knocking down row houses to construct bland dormitories. Thus I learned of the city’s powerful landmarks laws and of the importance of landmarking.

Many years later, after my wife and I settled in Park Slope and joined the Civic Council, I began to learn about the Park Slope Historic District and to appreciate the enormous contributions of Evelyn and Everett Ortner. I continue to marvel at the enormity of their accomplishments and at their continued engagement with preservation on an international level. Their designation report for the original Park Slope Historic District, in 1973, continues to be an indispensable tool as we put together each year’s Park Slope House Tour.

I only had the privilege to meet Everett Ortner a few times: at fundraisers for Develop, Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, and at Civic Council events. He even had the kindness to attend one of the early meetings of our Historic District Committee, when we had no idea what we were doing, in order to share his advice and insights.

Each time I met him, Everett urged us on to greater efforts to expand the district. He never failed to renew our sense of urgency; he insisted that we not fall back into complacency and take our beautiful neighborhood for granted, but to actively campaign for its protection and preservation.

Thank you, Everett — we truly stand on the shoulders of giants.

— David Alquist, a former Civic Council trustee, helped launch the successful effort to expand the Park Slope Historic District beyond its original 1973 boundaries.

‘Now, this is a long story. Are you ready?‘

Online: The New York Preservation Archive Project’s oral history with Everett and Evelyn Ortner, conducted in 2003. You can read the interview at www.nypap.org/content/everett-and-evelyn-ortner-oral-history-interview.

Plus:

“Preserve and Protect,” a look at how Everett Ortner’s legacy continues, by Historic District Committee Chair Bray

from the Summer 2012 Civic News